Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of articles written by Feigy W. Rosenberg, daughter of the late Gregory Weiss, who was one of the co-founders of the APBD Research Foundation. Feigy shares from her heart, hoping to help other young people who are growing up in a family where a devastating disease is constantly present.

To learn more about APBD and the APBD Research Foundation, visit www.apbdrf.org.

A special thanks to Barbara Schultz for contributing to this story.

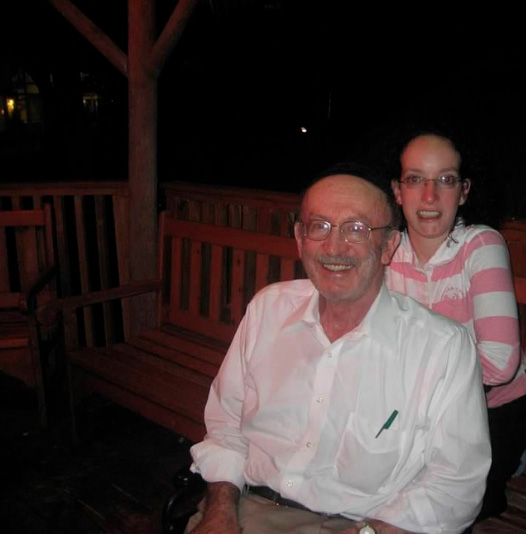

I was an only child entering my teenage years when I learned that my father had Adult Polyglucosan Body Disease (APBD). APBD is an ultra-rare, neurological condition which mainly affects Ashkenazi Jews — those having Eastern European roots. APBD would eventually rob Dad of his mobility and virtually every aspect of his normal, independent life.

“Watching him struggle with this crippling disease filled me with worry and sadness. We were very close, and I

cared deeply about him. I felt it was my duty to take care of him, to protect him from a society that often judged him for his disability.”

During visits to doctor’s offices, nurses and receptionists — who should have known better — often spoke past my dad to my mother or me, just as if he wasn’t there. He was a brilliant man who once held a teaching position in the Nuclear Medicine Technology Program at NYU, so becoming invisible was especially demeaning. I resented their hurtful ignorance. They assumed that because physical disability was present, intellectual disability was, too.

The disease brought me to a state of intense anger. How could this happen to my father? How could someone I cared about get so sick? It did not seem fair; this wasn’t supposed to happen to us. My dad was never the type to speak to anyone outside the immediate family, much less a therapist about his struggles with a disease. But unknown to me, anger brewed in him, too. This new normal proved challenging, for three people who cared deeply for one another.

I should also say I had a another feeling that didn’t seem to belong with the anger and resentment. A sense of pride. I was proud of myself for being there for my father, pushing his wheelchair home from the synagogue and going to doctor appointments with him. I was happy that outsiders saw and acknowledged I was doing my best to be a good daughter. Knowing that others noticed helped me a lot.

But sadly, I also came to realize that a stigma was attached to having a parent with an adult-onset disorder confined to a wheelchair. Dad knew, and I became aware through high school biology, that a genetic disease in a parent might affect the child as well. My father wanted no one to find out that his ailment was genetic in its origin.

Get research news updates from us!

The negative impact on my future became starkly apparent when I began the college application process in my senior year of high school. I wanted to dorm with friends at a university not terribly far away, but my mother needed support. She told me she simply couldn’t take care of Dad alone, so I would have to settle for a college nearby. I wasn’t happy, and my grades often suffered due to stress.

Then came my early twenties when I started dating with some frequency. But after only one date, or maybe two, the fellow would see the wheelchair and contact would cease. Without getting to know me or my dad, we had been judged.

In 2005, we went to Israel to see Dr. Alexander Lossos, the research physician who had discovered much about the mechanisms of APBD. He confirmed a suspicion I’d been holding in my heart: that I was a carrier for APBD. Fortunately, he was able to assure me that I would not have the disorder itself.

We went home. My father hid the truth about APBD from his own community and went about organizing the APBD Research Foundation to search for answers and to help others who also had this awful burden to endure.

When I was 27, I met my future husband, Mark. He didn’t seem to see the wheelchair or the APBD so much as he saw the person who was my father. He and Dad became quite close. As time passed and marriage became likely, Mark and I went for genetic screening. It was just a blood test — no nerve biopsies or other difficult tests. We learned that Mark is not a carrier, so our children cannot end up with APBD.

Thankfully, progress has been made in recent years. Now, a simple saliva test can identify carriers as well as diagnose people who have APBD. The internet is improving awareness in the medical community, so correct diagnoses can be made faster than my father experienced. Research projects are underway, too. However, much remains to be done, particularly in the areas of community education and, of course, treatments and a cure.

Now, I look at our five beautiful children who will not have to endure the anger, fear, disappointments, and judgments that I endured. Why do people so often assume that physical disability goes hand in hand with intellectual disability? Why would people refuse to get to know me simply because my father was seated in a wheelchair? What will turn around these attitudes?

People are fragile. Handle with care.

Get research news updates from us!